Jaime, The Unexpected in Portuguese Cinema

António Reis Interviewed by João César Monteiro, 1974

Translated by Andy Rector

This interview was conducted in the Spring of 1974 and went to print in the cinema weekly Cinéfilo mere days before April 25th, 1974, the date of the Carnation Revolution in Portugal, when left-wing soldiers revolted and refused to protect the fascist-colonialist Estado Novo regime, initiating a coup that ended 48 years of fascism under Salazar.

In his introduction, João César Monteiro writes:

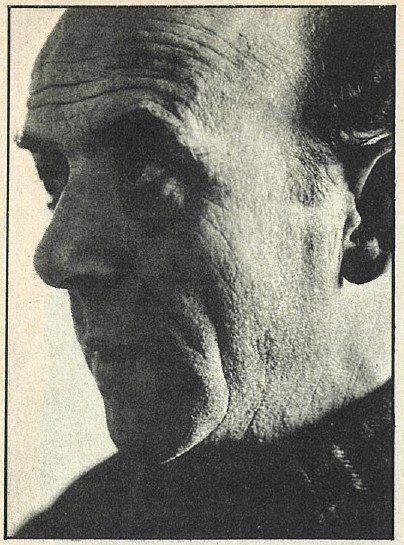

“What’s certain is, on a cold December afternoon, when I went to the Tóbis screening room, I was welcomed by one of the most candid and affable creatures on the face of this taciturn earth. But I didn’t grasp the true dimension of his qualities (and I say this with a hunch about how terrible the manifestations of their opposite must be) until after having seen the film, as if the film were the only possible and unambiguous revealer of this quite vehement and natural explosion of human greatness.

I’m talking about António Reis and the day I first met him, which by professional chance coincided with the first time I saw Jaime, for me one of the most beautiful films in the history of cinema, or, if you prefer: a decisive and original step in modern cinema, an obligatory point of passage for anyone, in this country or any other, who wants to continue the practice of a certain cinema, a cinema that only admits and recognizes its own austere and radical intransigence.”

Read Monteiro’s full introduction here.

With immense thanks to Andy Rector for proofing, revising, and annotating the text; to James Dias for his initial translation work; and to Raquel Morais, Stoffel Debuysere, and Courtisane for their collaboration. Their new print publication In the Midst of the End of the World: António Reis and Margarida Cordeiro features a different version of this translation and many others by and about Reis/Cordeiro appearing in English for the first time.

This text accompanies Peasants of the Cinema: António Reis & Margarida Cordeiro

João César Monteiro: I’ll refrain from asking when you first became interested in cinema, but when were you able to first start working in cinema?

António Reis: At the Cineclube do Porto we started by doing a bit of research on cinema theory, and, with the help of some friends, we tried to start an experimental film unit, although cinema already interested me before, as a form of aesthetic expression.

And, in practice what did that commitment, so to speak, concretely translate into?

We limited ourselves to a 16mm camera, collectively planned a particular subject together and rehearsed the first steps of carrying out a film, but with no accountability to anyone––we were bound only by a spirit of teamwork. We were unprotected, with no outside help whatsoever. Nothing. However, it was an experience I consider to be decisive.

Did you finish any of those films?

The group effort resulted in O Auto da Floripes (1963). We collected some material in the Barroselas region (Viana do Castelo).

How was the group work organized?

As our basic material we had the Auto* text, which was published in Vértice magazine. From there, we adapted the text according to what seemed essential to us cinematographically, without alienating the theatrical character of its expression. We also considered that the filming would be subject to the Auto’s contingency of only being performed once, which nixed any and all chances of retaking shots. That meant the crew had to travel back and forth a few times to get a thorough geographic understanding of the area. For example, we measured the land and studied where to place the cameras, aiming to gather a multitude of points of view, a bit like television, and in fact we worked with four cameras.

After these scouting “raids,” we restructured all the work we had previously done and, one fine day, we filmed O Auto da Floripes. The crew set off the day before to Viana. Strategic positions were taken; we used two fixed cameras for the wide shots and two handheld cameras at the level of the stage platform, so as not to disturb the audience watching the performance, and followed the actors as they moved about. This entailed knowing the Auto and its scenic space beforehand, and therefore led to an “a priori” cutting, which didn’t end up being the final cut, but, in any case, was a kind of reference for the final montage of the film. There wasn’t really a creator per se, it was a real team effort, with everyone participating to a greater or lesser extent. As I said, it was a decisive and quite important experience, though today I can’t evaluate the aesthetic result of the film. However, the spirit of loving our work, the self-sacrifice and selflessness of everyone involved, was unforgettable. We really went after it, night after night. The boys would leave their very tough day jobs and concentrate on the film work every night until the wee hours. Nowadays that might make a professional filmmaker laugh, even a filmmaker from Lisbon, but I believe everything in life begins seriously like this.

[*Auto da Floripes, or the Floripes Play: a popular performance dating back to the 17th and 16th centuries, forming part of the pilgrimage of Our Lady of the Snows, held every year in the first days of August in Viana do Castelo, northwest Portugal. The performers are local people, and the show––a mix of pantomime, recitative and dance–– takes place outdoors, in the square in front of the church, involving Christians and Moors.]

I’m not from Lisbon, so please excuse my insistence, but I’d like you to go into more detail about your geographic scouting, with regard to O Auto da Floripes.

In the same way that, today, we know to work on the ambience of the light, the focal lengths, and so on, we knew that the timing of the theatrical performance was a major constraint on the film’s “découpage.” We also knew that the Auto had its hot spots, its pivotal points, from both a theatrical point of view and as a potential cinematographic transposition, which ought to be free, as much as is possible, from any sort of ambiguities of language. This placed an almost a priori obligation on us to never fail to spot the vital bits. Those big, choreographed movements, those medium shots of actors or groups of actors were, at a certain point, no longer theatrical but cinematographic. We weren’t naive, we were already expecting a wide range of problems and, for that reason, the scouting we did was extremely useful. We also contacted the people who would play in the Auto and saw them in their daily life. One was a tailor, another a farmer… Of course, the film has a very basic gathering of ethnographic aspects, which we can laugh at with a certain bonhomie, but that’s secondary.

In any case, that experience must’ve been very useful for your collaboration on Manoel de Oliveira’s Acto da Primavera (Rite of Spring, 1963).

To a certain extent. Sometime after our work was finished with the experimental film unit of the Cineclube do Porto, Oliveira invited me to be his assistant. I was a bit surprised, but I started working with him. However, I’m more like a tributary; I learned more from watching films and the plastic arts than I did from that job, with all due respect to it. The plastic arts, music itself, poetry itself, were crucial to me. Cinema is an art that touches all the others, without being their sum. There are, nevertheless, huge implications, and one ends up acquiring a cinematographic spirit, and later becoming independent, and that, in fact, is learned in the exchange with the other arts.

THEY SPEAK WITH TREMENDOUS GRAVITY

AND ONLY SAY WHAT’S STRICTLY NECESSARY

Is the dialogue you wrote for Paulo Rocha’s Mudar de Vida (Change of Life, 1966) also the result of previous research?

The nature of the dialogue in that case comes from a very concise style that I have in poetry: its gaunt appearance is also particular to the fishermen of the Aforada region, which I know. It has a certain kinship with the way people speak in that region, because they speak with tremendous gravity and only say what’s strictly necessary. In addition, Paulo Rocha was taking on a subject I’d studied when I was a teenager, and that was very important. Practically speaking, I’ve always seen dialogue in the way people speak. That’s why there are a lot of silences, a lot of staccati, a cinematographic punctuation. In fact, I believe I created a dialogue specifically for the cinema. Luckily, I was very economical in my poetic expression, and aware of the bad habit of using dialogue as a crutch in many films. I was alert to that kind of danger. Anyhow, I wrote the dialogue with great spontaneity, almost without feeling the need to retouch them. It was as if I recognized a discipline, absorbed that discipline, and was able to write without constraints. I also respected the time an image was going to have, the space it would involve, etc. Intuitively. And, strange as it may seem, I saw Paulo’s film beforehand. My vision certainly had nothing to do with the film I saw later, but that work gave me great visual discipline.

Was there any research done on popular words and expressions?

No. There wasn’t any done at Torreira, but there are no differences of dialect between the inhabitants of Aforada, who come from that whole Atlantic side, and the inhabitants of Torreira, where Paulo’s film is set. There are, of course, small differences, but not the kind you’d find, for example, between someone from the Trás-os-Montes region and someone from Alentejo. They’re more than cousins; they’re brothers. And while there are certain differences as far as technical tools are concerned—I’m not a good judge of that—there is a great kinship in their vocabulary. And there’s the presence of the sea. They have the same broad gestures, the same violence of life in and around them, the same dependencies, the same furious passions. When Paulo spoke with me, I agreed to write the dialogue, because I was going to talk about something I had experienced, and experienced during that free dreamlike period called adolescence.

I worked with those fishermen for many years, at sea, in fishing boats, in trawlers, which gave me many fruitful experiences. I spoke like them. Even today I can still imitate their speech, and I wrote a book about them that I never published and that I assume was destroyed. It was a great lesson for me. If Paulo had asked me to write dialogue for a film set in Lisbon, I definitely would not have done it. At least at the time. A fundamental human reality exists and, as linguistics has given us such great responsibility, I believe, more than ever, that one must be deeply serious about adhering to dialogue. Not only out of respect for linguistics but also out of respect for the cinema. People have been deeply complimentary about it. I would like to rethink all the dialogue I’ve written, based on that film. I would like to learn from the mistakes I’ve made.

THEY SAY THE SAME “THAT,”

THE SAME “IF,” BUT…

What do you think of the Portuguese spoken in Acto da Primavera?

I don’t think it’s the Portuguese from Trás-os-Montes. I find it difficult to explain… perhaps I could do it with a practical assessment. I could answer that question if I saw the film again, if I reread the text. But the impression I have is that although it is represented by the people—which doesn’t necessarily mean anything—it’s a representation of things which are not popular. It has an erudite or pseudo-erudite tone, a parochial and literary tone which, orally, suffers in transposition, similar to the way an erudite painting made by a popular painter suffers. But those men don’t speak the Trás-os-Montes language that interests me. Neither archaic, nor modern. Of course, they say the same “that,” the same “if,” the same tirades that people say every day, but…

Besides, we only need to make a comparison between what’s in the text, the way they speak it, and the great tradition of oral or written poetry in the Middle Ages, for example, to see where the forgery lies. Acto da Primavera has some authentic parts, but it really isn’t like a chestnut tree. It’s neither Terra Alta nor Terra Baixa [highlands or lowlands]. What I’m saying is a bit controversial and might make you smile, but I presume it would definitely prove what I’m saying, if I were asked to prove it. This is an aside, but I don’t believe Rodrigues Miguéis’ attack on the text was done out of malice, because that wasn’t the issue. Manoel de Oliveira was deeply honest in what he made and he fought hard to make the film, as we all fight for anything serious, but the text probably doesn’t deserve that much respect. Neither because it was played by the people nor because it is part of a tradition, a tradition still being maintained, more or less pseudo-mystically, like a kind of cyst embedded in the province.

Well, yes, there’s no doubt that the influence of the Church in rural areas is overwhelming.

That’s plain to see, but if we want to reach much deeper roots, I’m convinced that its influence in Trás-os-Montes, like anywhere else, is episodic. No matter how painful that may be to some.

But don’t you think that the imposing character of a given language can be subverted by the simple fact that its phonetic, gestural, etc., representation is produced––even if in a repressive way––by a social class and context for which it was not initially intended?

I’d say that they do a lot with that text, the way they pronounce and speak it. Besides, for those who don’t usually perform the play and that Oliveira chose for the main roles (for example, Nicolau who played the role of Christ in the film), the filming was an extremely arduous learning process. I witnessed the effort of the actors and the effort of the director who demanded they modulate their voices, express themselves phonetically, etc. It’s clear that, in spite of this work with the actors, the local dialect remained in terms of pronunciation, but not in its linguistic and atavistic construction.

Still, the shot where the mother of Christ sings with all the liturgical weight of the litany that amazing chant “ai dolor” told me more about Trás-os-Montes, about this entire country, than the most eloquent of “live on the scene” reports.

That’s very beautiful. And that tracking shot of the two apostles, Peter and John, too. But look, you’re already looking for an “ai dolor, ai dolor” which takes us to something very authentic, in our poetry and in our tradition. With a mystic charge, etc., but, in reality, when we talk of “ai dolor,” we’re probably not far off from the roots of a genuine language and from the cantigas de amigo. But as for the other rhetorical charge and those sort of verbal frills… Of course, they can be used as rhetorical and eloquent factors: articulations that art, in other times, also used brilliantly. But it’s fallible… it depends on the filmmaker, and how they use it.

At times Oliveira gets carried away with the text’s fascination. He’s attracted to a kind of musicality (not to be confused with the spirit of the music), by the sweet-sounding aspect of the word, and he doesn’t clean up the spurious elements of the text.

The text was respected because what interested him was its pathos, and even its literary and mystical expression. The film—which is essentially Romanesque—goes from Romanesque to Gothic, precisely in those more heraldic and eloquent moments. There is, in Acto da Primavera, a hybridism that’s played up in that sense. In fact, Oliveira and I once discussed this, and he completely agreed with me.

IT’S ENOUGH TO LOVE

A LITTLE CYLINDER

Now, let’s move straight on to Jaime. What interested you when you chose this subject?

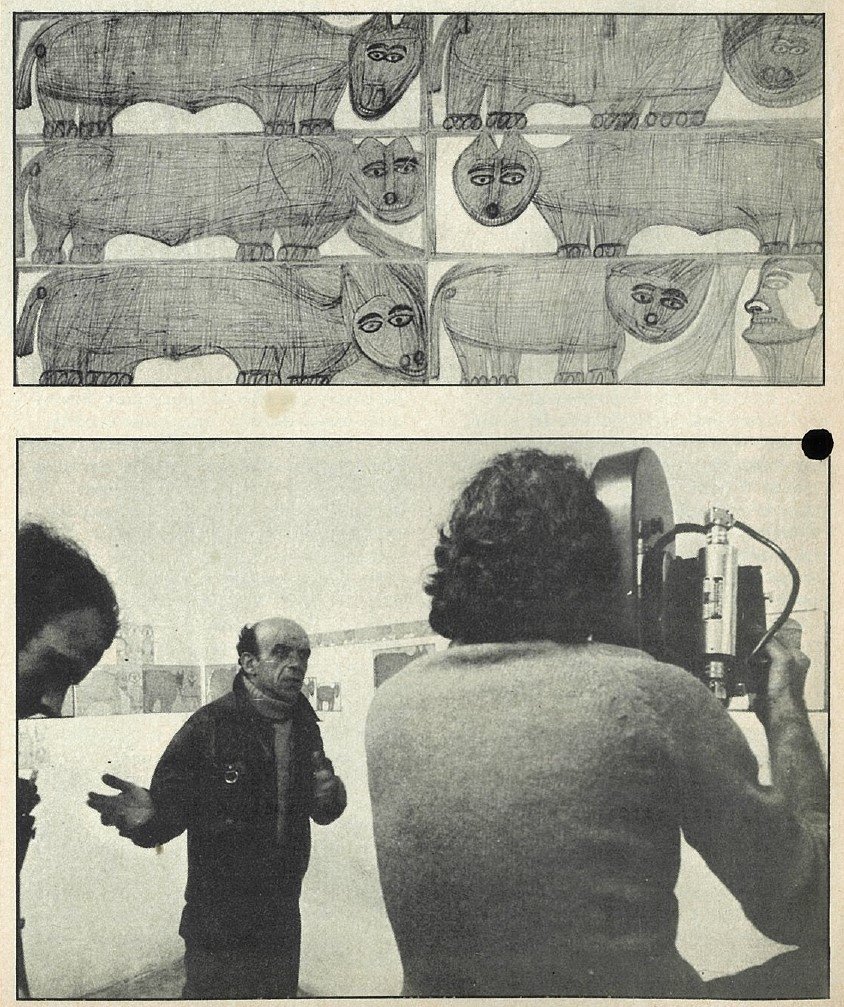

Above all, I was interested in this man’s life and, sentimentality aside, it seemed to me it could only interest other people if we could convey this man’s life aesthetically, since he couldn’t really defend himself, or attack alone, or because this may not have even interested him. I don’t know. If you ask me why, I would say that I identify with his conflict and that practically everyone in Jaime’s condition can identify with this conflict. I can also say that I was trying to make a film with a humble approach: my goal was to at least safeguard on film the drawings he left behind and that I find brilliant. If it had been a work of pure filmic archaeology, I would’ve been happy, since I know that a large part of his art has disappeared.

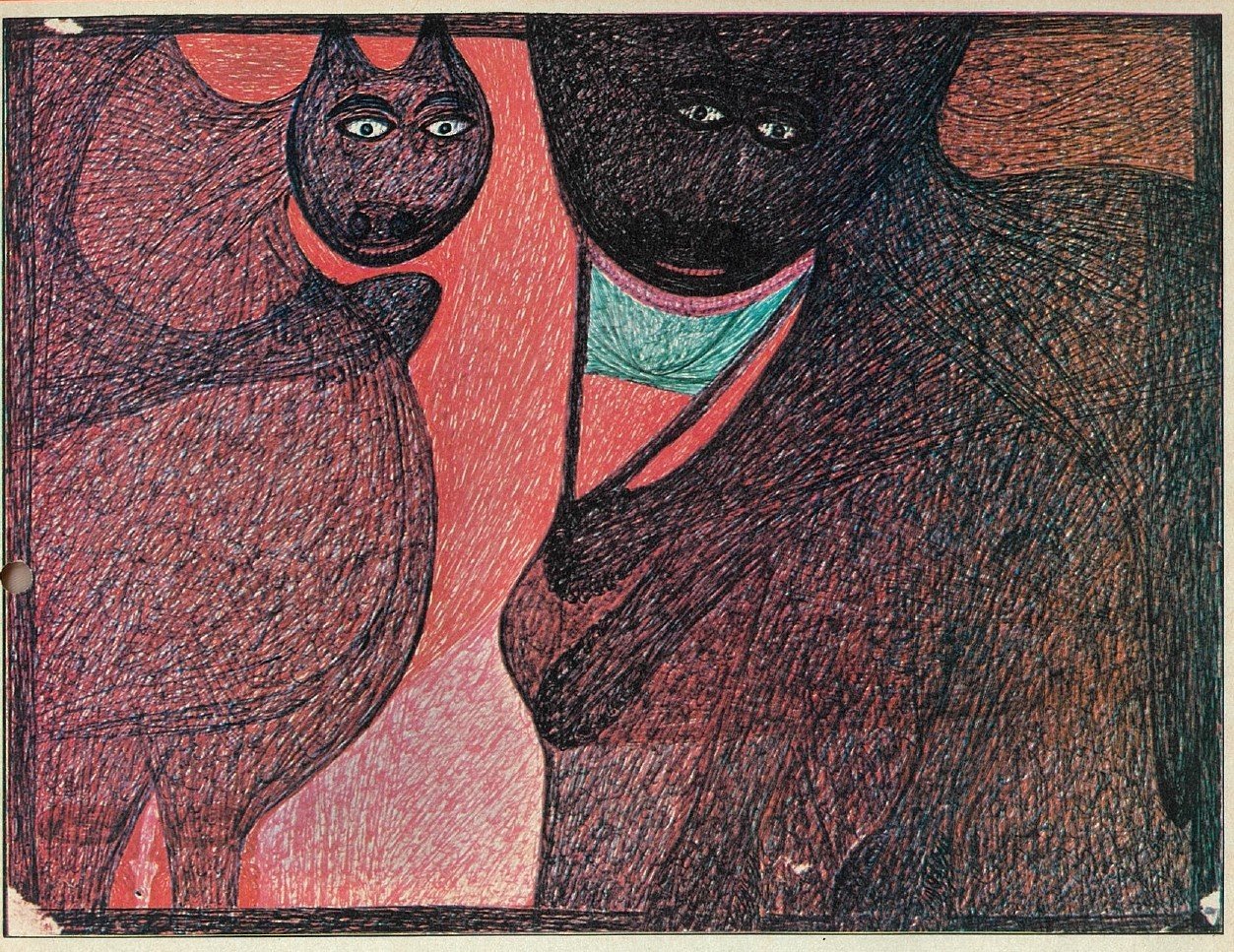

I’m not an expert in the plastic arts, but to me it seems undeniable that we’re faced with a pictorial universe of extreme richness.

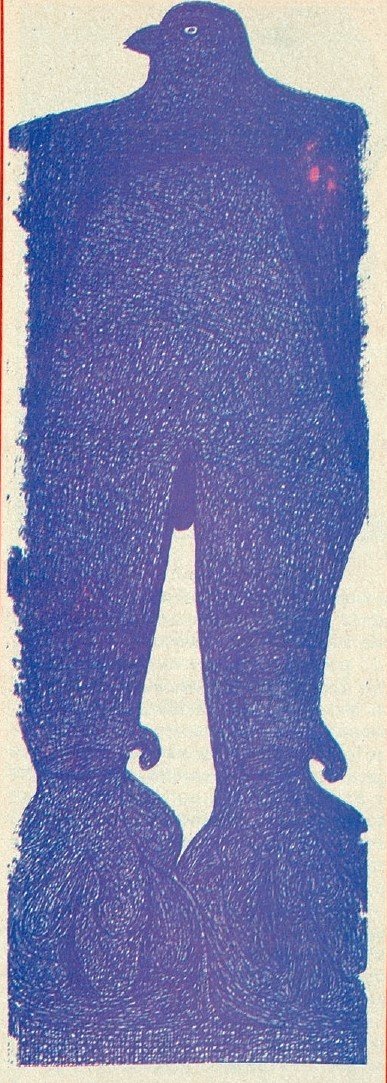

I believe it’s enough to love a small cylinder seal from Mesopotamia to “feel” that Jaime is an artist of genius. But those who are excited by those ancient clay seals are also excited by the paintings of Lascaux, Altamira, Giotto, Rousseau, Léger, Séraphine Louis. . .

Jaime’s bestiary, which is Aurignacian and Magdalenian, and, at the same time, a parade of archetypes, is one of the most unique bestiaries in the History of Art. And his “fauve” or expressionist aesthetic owes nothing to those European movements, and anyhow he was not their contemporary. His historical and psychological time was different. His cave-like subterranean and sidereal space was different. His clouds with 1000 men inside who traveled, dreamed, and suffered, were different.

So we have on the one hand, your interest in the plastic arts…

I was always very interested in that, but I’ve never been able to see Jaime the painter as separate from Jaime the man, which posed a problem: Jaime started painting when he was sixty-five, and up to then he’d had a whole life, and I couldn’t pinpoint what had caused those paintings. But when I studied his life more closely, the place where he was born, the place where he was hospitalized, I saw that his painting was deeply determined by those factors. And because works of art are painted by a person (a line is drawn under emotional pressure), I was interested in finding out what was behind the painter. Maybe in that way I could find a deeper meaning, and not confuse things. That’s not to say that those who know nothing about Jaime’s life can’t appreciate or evaluate his work, but if it’s true that a visual symbol represents something, concretely or abstractly, then the struggle for that representation is a struggle to find its poetry or its dialectic. What we tried to do was more of a dialectic of Jaime’s paintings, with all their poetic, dramatic, and biographical implications. That’s why I think it’s unfair that Jaime isn’t fundamentally considered a film, a fiction film. It’s not a story, but it’s a film where everything is important. Even its bare appearance, stripped of any preciousness. It seems to me unjust to a work like this to support it with affectation. I don’t want to excuse the lack of gloss in the film, the lack of retouching, but there was a kind of modesty that governed its aesthetic conception. I also worked with ballpoint pens.

GIVING HIM THE DIGNITY OF A STATUE

That kind of modesty that you, quite rightly, refuse to dissociate from the film’s aesthetic conception seems to me to profoundly resonate throughout the film’s global movement, and this is evident right from the beginning, when the camera is positioned facing the asylum’s courtyard, obediently reflecting a moral order which we could consider as the search for the right place for the camera—the place that simultaneously destroys the notion of a border, the same way that it destroys the very rectangle of the frame and prepares us, in a way, for a series of circular games, with no beginning or end, where the entire filmic space is articulated.

You could say that when you peer into any place, you are haunted by what can be seen and what can’t be seen, and you can’t show the whole space. It’s a visual selection, there’s no sprawling out. The commitment to using a handheld camera which represents, to a certain extent, the disarmed human eye, seemed to us the right way to achieve a kind of rawness of observation. The perspective itself scarred us, in depth of field and everything that involved transitions or modulations. There’s a kind of woodwork quality to the shot, reduced to its essentials. Obviously, we could have done it in a continuous sequence, but that would’ve meant a lot of filler in the middle, and I wouldn’t have been able to direct the patients in the way I did, achieving the sublimation of an oligophrenic, giving them the dignity of a Henry Moore statue. A dignity that at times the illness doesn’t allow, and that many people are disgusted by; but it touches me deeply, as a human being, because of the fatality and wonder that it is.

Another thing that particularly impressed me in the film is the fact that illness is never present.

There are no patients in the film. No one is normal or abnormal.

The only reference is the uniforms. In the barbershop shot, for example, the work gestures of the professional barbers and the patients are the same, and we only distinguish the real situation because some are wearing uniforms and some aren’t.

In that frieze, I wanted to focus on the fact that you can find the most admirable figures there, figures that could be compared to the great Romanesque or baroque statues, or to everyday men. Apart from that, the only concern I had, and it may be a moral principle, was to blur and destroy the border between normality and abnormality, with no “parti-pris,” for the simple reason that it’s in my blood and in my intelligence, and especially because I’m convinced that most of the abnormal are roaming around out here, and many normal people are hospitalized. I classify that division, in the extreme, as racist. It’s one of the great problems of our time, anywhere in the world, and to try to destroy that prejudice was, for me, very important. We should certainly think very hard about the privileged social place that the so-called mentally ill occupy in the communities studied by anthropologists. I worked among them with great joy. They were admirable in everything I asked of them and everything they helped me with.

THEY ARE NUMBERED MEN

And wasn’t there, at times, some strangeness and unhealthy curiosity coming from the crew?

Maybe just strangeness at first, upon initial contact, but then they all felt as if they were among friends.

The end of the panning shot in the barber shop, you mentioned it as a frieze, and indeed the characters are actually arranged like in a frieze.

It’s still a metaphor for Jaime's painting, and we hear his obsession and fascination on the soundtrack. And the characters we see are the dark characters Jaime claimed to paint. In his expressionistic painting there’s a counterpoint between the animalistic and the human. The animalistic parts are archetypes of the countryside, from any age, and those expressionist characters are not only his fellow patients, but the comrades of any barrack, from any hospital, not only the insane, from any prison, any orphanage, etc.

They are, we might say, numbered men. The frieze that appears at the end of the panning shot is of men subjugated to the orderly. An orderly from that age, or any other. The film is contructed by going in and out of the drawings. I mean, there aren't drawings on one side and real life on the other. You go in and out freely. It’s part of a unity that makes up the film. In the directing, there is a stylization of and in Jaime’s characters, and through the stylization employed, the reality of the hospital also ends up being reflected.

For example, in the whole opening sequence in sepia tones, all those characters were not directed to be beautiful—although it was important for me to achieve that—but directed with the same rigor that a director directs his professional actors. This wasn’t for the sake of the strictness of the raccords** or the film’s rhythm, but for the ascetic strictness that the characters’ have in the nobility of their attitude, a plastic asceticism that Jaime also gave them. That might be the reason we were able to achieve a general atmosphere between the plastic arts and reality, through their mutual interpenetration. The characters become both more human and more like sculptures.

[**Raccord roughly means a “relation,” “join” or “connection.” It’s used here by Reis in French, and in general usage as a cinema term by French and Portuguese film workers in film production and film criticism. Like découpage or mise en scène, raccord deserves to remain in French and, case-by-case, understood in its complexity and multiple forms. Raccord is often reductively translated in English as “continuity” or “matching,” or “continuity cut” or “match cut.” Indeed, practical French/Portuguese usage of the word on film sets somewhat adheres to that translation, i.e. it indicates the search for or achievement of smooth continuity between the space-time of shots, in actions and gestures, of hair and costume, etc., all those things in dominant cinema that must be made to match “naturally” in the highly unnatural, discontinuous medium of film. But raccord as used by Reis should be understood more expansively, as a more total and transformative process on many levels (chromatic, epochal, sonorous, etc.)––about which this interview and Jaime are definitive. The raccord, the linking of things, colors, stories, peoples, sounds, eras, etc., across the time and space of a film is the crux of Reis/Cordeiro’s cinema. In his text on Reis/Cordeiro’s Ana (1982), critic João Bénard da Costa calls it a “fabulous raccord” when Reis cuts from people eating big slices of watermelon to a procession of geese. What "links" or "matches" those things except for the act of editing itself, made during a conception of the world? Indeed Reis somehow makes these two things that do not resemble each other––fruit and geese––rhyme and relate inexorably, and in this case, towards “a great peace.” As Ricardo Matos Cabo wrote, Bénard da Costa, César Monteiro, Reis/Cordeiro “perfectly understand the liberty of montage and raccord, the associative nature between two disparate images and the immense possibilities for a narrative of unity between them.” –– Andy Rector]

THE FILM’S GREAT SPRINGBOARD

There’s a fabulous part in the sequence that opens with a figure, wrapped in a colorful shroud, in the foreground. One could say that this character’s grave, raised-arm gesture is what commands it all, introducing a new dimension to the film. It seems to command the action.

That figure is “God.” For me, it’s one of the most complex sequences in the film. It begins as a metaphysical sequence. It’s implied in the previous sequence. That door with the play of light and shadow at its converging point is, really, a kind of death alluding to Jaime. It is, if you like, the “Beyond.” It’s also a theater, and there’s an explanation for it. It could also be recreation time for the patients. For the director himself. It’s a sequence that gives me food for thought, to this day, but above all it offers the possibility of entering into the transfiguration that takes place later in the film. It’s the film’s great springboard, as it begins very seriously, then becomes banal, with what we see in the washroom, but then we suddenly understand that it’s Julio de Medici’s tomb, as all that alabaster is transformed into a secular tomb. It is a very dignified death.

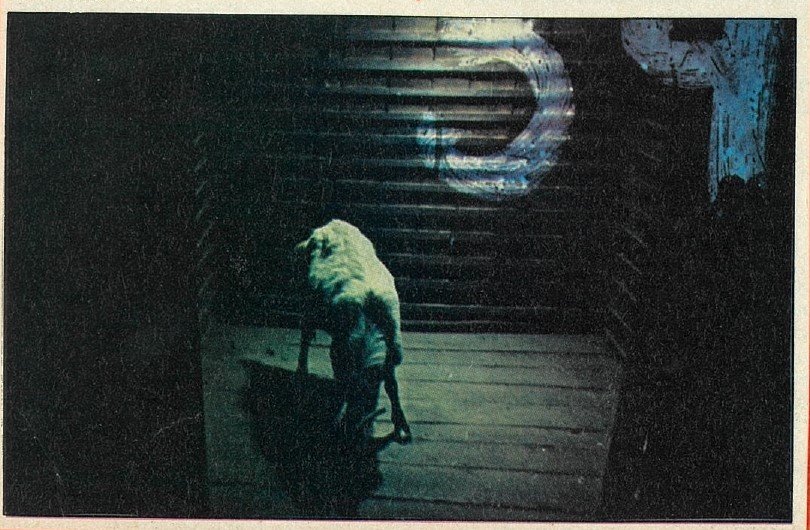

You go from exterior to interior with a handheld tracking shot that ends at the bottom of a bathtub and makes a raccord…

…with the boat. That sequence is, so to speak, a descent to Lethe, that little dog that we see is a burial for Jaime and, simultaneously, the entrance to the hospital. If you remember, there’s a river of letters that acts as a counterpoint to that river and is a raccord to the drawings. It’s also the introduction to the drawings.

So, the bottom of the bathtub connects to the bottom of the boat.

And when you get back to the little dog, there’s muddy water, similar to the brown stains in the basin of the bathtub, among other things. The film’s chromatic raccords are as important as its dynamic raccords, and they serve the dynamics demanded by the film, dynamics similarly required by the plastic arts. These raccords are made of either kinship or contrariness. Sometimes the film looks as if it’s come undone, but it hasn’t. In those moments, other values are being considered. It’s the same with the sequence of the little boots. Suddenly we’re in Assyria, with all those feet that are a visual representation of Mesopotamia.

That’s also related to a purely musical punctuation.

What fascinated me was when I felt that the different mediums were constantly provoking each other, without being autonomous. The film always escaped us. Jaime also seemed to escape.

Like all those who leap into the void and go through multiple deaths.

Actually, he does die several times. In one caption he says he died eight times. In other writings he said he died almost 100 times. It’s like us, who die a little every day. He himself felt he had died many times there. We can analyze this from the point of view of delusion or the diagnosis of his disease (Jaime was a paranoid schizophrenic), but in our lives we also say this countless times. We die and are reborn, like in that final tracking shot. It’s the Renaissance, Assisi, Giotto, Fra Angelico, it’s the lustral water of a meadow, of flowers, it’s, again, the entry into the nettles that gives us flowers, in the final part.

It made me think of the great poets of Soviet cinema. Perhaps Dovzhenko…

I only know Potomok Chingis-Khana (Storm Over Asia, 1928) by Pudovkin and Ivan Groznyy (Ivan The Terrible, 1944) and Aleksandr Nevskiy (Alexander Nevsky, 1938) by Eisenstein. And a thing called Vesyolye Rebyata (Jolly Fellows, 1934) by Aleksandrov. I haven’t seen many.

Me neither, but anyhow what impressed me was just how fast that tracking shot is. Suddenly the whole space opens up, at the top of its lungs, to everything, with an unusual energy, quite unusual on these western shores…

But if you recall, we were almost always in a neutral space, a plastic space, a closed architectural space, a space at times obsessive.

THOSE PEOPLE CAME FROM

WHERE THERE WAS HEATHER

But you continuously break the tension of these claustrophobic spaces! Although you do it differently, without the screaming tone of cosmic provocation that defines the tracking shot. I’m thinking of the tender insertion of a shot of heather from the outside, into the asylum courtyard sequence, which is also, in the film, the first introduction, the first note of color or, if you like, the first chord of color.

Even so, it’s a sentimental raccord, with the petting of the little cat and also the sepia of that space, it’s a kind of call: those people came from where there was heather, or where you can still dream of heather, or despite the conditions those men live in, there is still heather, there is still water. Or there must be! Maybe that man who pets the cat once had one, or maybe he’s petting the heather. It depends on the delirium of the viewer. I don’t know. I can’t officiate.

The presence of a separation between beings and things, the blatant brutality of that split, is particularly pressing in the film, and I think that when you speak of a sentimental raccord, you’ve touched on its deepest movement—that of an evocation (and not only nostalgic) of a lost unity. It’s useless to recall that this is perhaps the most fertile tendency of all modern art, from Rimbaud to Klee, passing through, I don’t know, Pessoa, Brecht, Godard, Joyce, Stockhausen, Char, etc. And I believe I wouldn’t be mistaken in saying–– and don’t take this as enthusiastic adoration–– that by fictitiously restoring that unity, you invented the most beautiful faux raccord in the history of cinema, in my humble opinion.

Today we’re like people who’ve been burned. The anthropocentric conception is being overcome so much later than in millenia-old civilizations of the past. It’s as if we’ve woken up too late to realize that man is a very tiny part of what’s called earth, a great phenomenon of life in the universe. I, a man, am small. And it is immense…

A BIT LIKE WHAT KEATON DID WITH GAGS

Let’s talk about the water. The variations of the intensity of water, the distribution of fluid regions throughout the film, it all obeys values very similar to a certain formal research in modern music (I’m thinking of Stockhausen), but it also provides a very fruitful inventory of a structural anthropology of the imaginary.

Sometimes it’s just the water we drink, other times it’s the flood waters that drags us away. In Jaime’s case, the use of water is due to it being an obsessive element in his writings. He was born on the banks of a river, he often fished there, he often watered his fields with that water. In the film, water is a symbol, even in its very color, or course. Take the water in the fountain. It’s a normal fountain, but when I saw it, it seemed a terrible thing to me. Today I think it’s essential that fountains exist in that place. Suddenly, it’s the thread of life, an hourglass. It’s a water that that god, so to speak, orders to stop. The water in the river is for the crows and the ripped-out roots and the knots in the tree trunks. When we see that panning shot of a mountain, a lot of water has passed through it, a lot of springs and fountains. And Jaime was born next to the Zêzere River and was always very connected to water. But if water allows an immediate denotation of meaning, it also allows for connotation, and I think the immediate meaning of every shot is essential, being immediately undone by the play of associations and contradictions that arise among them. In that sense, it seems to me that there’s a bit of what Keaton did with gags, that is, the film is constantly escaping one’s grasp. The spectator doesn’t have time to revel in it, or to hold on to those shots because they’re pleasant. They need to grasp them in the context of the whole film. There are some conclusions that they’ll only reach later, others they’ll eventually be forced to abandon. This has nothing to do with complexity. This is how we felt and worked. There’s no intellectualism of any kind. There is knowledge, but knowledge only used as a tool, to better provide for us, to achieve the end we wanted. It’s not a difficult film for a nonlinear film.

“I LEFT THE ARKS”

It’s a fascinating film precisely because it requires some heavy reading (which doesn’t mean it acquiesces to fascination, quite the opposite) and you patiently make sure to plant a few clues. So, I would like it if you spoke a bit about the sequence in Jaime’s house.

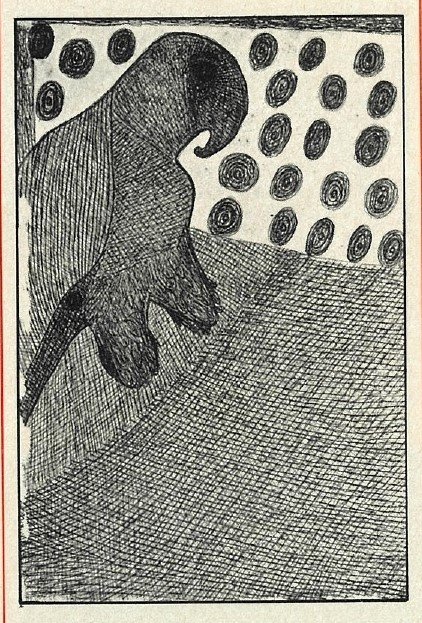

The arks. “I left the arks.” It’s the same as with the water. Apparently, it’s the wooden ark, but it’s actually the belly of an animal, a house you’ve left, a dream that was violated, a landscape that remained. When he says, “I’ve left the arks,” to me it’s everything he’s been forced to leave behind. The ark is enveloping, but he kept the arks open, he left the arks open to the elements, the proof of which is that, in the drawings, the animal figures are also arks. A boat is an ark. A house, with or without holes, is also an ark.

The final shot in that sequence, of the ceiling, closes that circle, but, meanwhile, its path can be followed in all its multiplicity of meanings: there’s the real, there’s the surreal…

If you take surrealism as man’s way to alter reality, to add to reality’s depths and heights––to understand that reality is not exactly the glass that we hold, but the glass that cuts us, the glass from which we drank, the glass that we transfigure––then that sequence is surreal: the shots’ ensemble of construction includes the walls of an ark, a cosmic ark, an ark of dreams.

The open umbrella, inside the house, on top of the pile of corn…

It’s not the Dadaist umbrella. The umbrella is an instrument of the poor. It’s a useful instrument, a poetic instrument. Our childhood is filled with umbrellas, from the threadbare umbrellas with little holes that four or five of us would always manage to fit under on the way home from school, to the umbrellas that always seemed to be sitting behind front doors. I don’t know. The knifegrinder’s umbrella at the market, the umbrellas of the cities without a raincoat, the great umbrella of the Far East… The umbrella is a mushroom, a tree, and there, essentially, it’s also black on yellow.

But don’t they say that to open an umbrella indoors brings you luck?

I’ve always heard: “Don’t open your umbrella indoors, it brings you bad luck!” Perhaps Jaime was unlucky there, but when he said he left the arks—and Jaime had delusions of gold mines—there couldn’t be (without paraphrasing Guerra Junqueiro) any better gold than corn. I hope one day the earth’s gold is corn and not the gold from South African mines. Suddenly, all those doors that were closed, they were all made of marvelous wood, and I remembered that I should give free reign to my imagination. In fact, when I was a child, I saw many corn cobs set to dry inside the house, because when it rained they had to be taken off the threshing floor. By putting the corn there, I remembered the umbrella, and by putting the umbrella there, I remembered the great modern chords of yellow and black; it all started to converge into a deep emotion. And then it was everything that the shadow of the umbrella dragged in, as all this was organized, both cinematically and plastically. Whenever Jaime was delirious, he took a pickaxe and started to pick at the cement of the hospital, to discover a gold mine. I had my delirium too. I took up the pickaxe… I’m not ashamed of it. Don’t forget that this sequence begins with us seeing through the eyes of a donkey, and immediately, the donkey’s eyes are human eyes.

You can tell it’s an animal, but you never find out it’s a donkey.

Yes we don’t know, but that beginning, without changing the shot, is an ellipsis. That animal’s eye is immediately the eye of an observer. When you see the first shot, in the house, it’s the little donkey that’s looking at the yellow corn and the umbrella, but when you see the next shot it’s automatically a person who’s peeking through a keyhole at Jaime’s arks. In a sense they’re also the arks of our childhood. And the word “ark” (arca) is very beautiful.

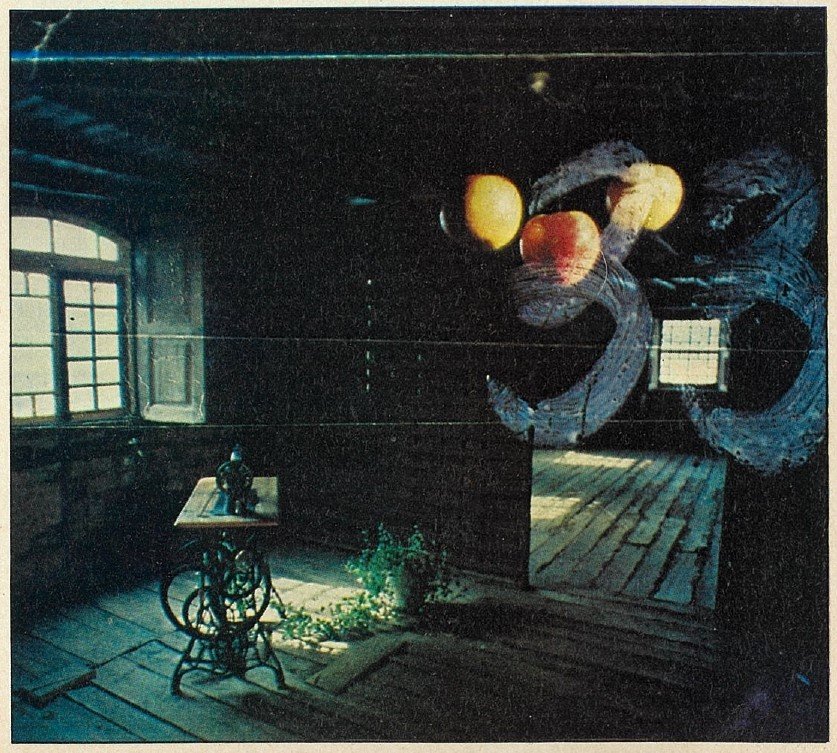

What about the goat? And the hanging apples? And the sewing machine?

They’re the three little golden apples. They’re three planets. They’re the necessary yellow in that overwhelming brown. The sewing machine is not Fernando Pessoa’s, nor that of the expressionist films. It’s… The apples are the apples from the village that are hung from the ceiling to keep them from rotting. I don’t know if you’ve ever been in a hayloft, but when there’s no fruit left, our uncles from the village would put the remaining pieces in between the hay, so it lasts longer, and you have fruit all year round. It gives the house a lovely smell! Everything was abandoned; it was the house that, in a way, Jaime had left. Yellow was needed in that house, we needed to bring Jaime three flowers. This sounds like literature, but if you want to call it innocence, or love for Jaime, then call it that, although in the film, you get a different meaning from the apples.

THE GENEALOGY OF A GOAT

It reminds me of a poem by René Char that I once saw written on a blackboard inside of a house that smelled, curiously, of apples. What about the goat?

If you want a mythological explanation for it, if you want to take it further, we can go beyond the Celts. Hell, if there are people who care about their family tree, I care a lot about the genealogy of a goat.

But to get to the Celts, it would’ve been preferable to get a pig.

A pig just wouldn’t fit there, in the poetics of the relationships. The goat was also Amalthea. And Diana isn’t far off. The gelder’s pan pipe is played by a shepherd, but she’s a bit like a Pan who walks those hills. She’s an actress as well. She’s a lost goat because Jaime was a shepherd. This still seems like literature, but as you see a lot of time was given to the goat. She even eats her own shadow. And hears voices. She hears voices. There’s a voice, in Stockhausen’s “Gesang der Jünglinge” (Song of the Youths, 1955-56) that starts for her. And it’s beautiful too. Visually marvelous. And she’s a goat stuck in a house. She’s also one of the arks. She’s an ark in an ark. There’s also that deep breathing she has. And there’s a closed space. There’s the great open ark we saw earlier, the big terrible open one, that’s almost like a coffin with a bed diametrically opposite.

To me, she’s the most beautiful actress in Portuguese cinema.

And she ends up eating her own shadow. It was difficult to pull off. You can’t begin to imagine the struggle it was to hold her in place. We had to carry her up two floors. And we let her live with us, like she used to live, in another time. Dignified. People only have pedigree dogs in their homes now. I don’t know why. They could have a goat. Picasso liked them a lot. And he was right. He lived with them, but he was plagiarizing. Even the goat’s poops were beautiful. I’m not joking. It’s a beautiful animal. Without the slightest hint of malice, they even asked us if we didn’t want her to bleat, to go “mé”…

You could’ve got her to go “Mé-lo Neto” [Brazilian poet]. Or maybe not, she could’ve gotten vain, too vain, or too sad.

I don’t know! Well, in the entire sequence there are only two colors. It’s all built on darker values—to contrast with the strong colors of Jaime’s paintings—where the lively color of the apples and the red of the yarn skein comes forward. Nothing more. These are those primary colors that painters, often with just one tone, use to hold an entire composition together.

A COLOR FILM ABOUT COLORS

Another aspect of the film that I find extremely interesting is its chromatic play.

To be precise, in that sequence with an apparent Telemann minuet, after the apparent pathos-soaked cry of the widow, there are a few shorter shots with shades of blue, and there’s a certain gracefulness, albeit threatened, in the minuet…

I’m sorry for interrupting, just as a parenthesis: in the shot of the widow, when you feel like she’s reached the limit of her emotional strength and will breakdown and collapse, you cut the shot immediately…

I filmed that shot six times, but it’s very difficult to ask a 71-year-old widow to call for her husband as if she were in the fields, when on top of that at thirty-something she’d been left with a litter of children.

Her tremors are very strange.

She really has them, but we were digging up her husband. Sometimes she would scream for him in the middle of the fields. She had suffered a great loss, and after so many years, we suddenly show up, knocking on her door with all our gear, wanting to make a film about her husband. You have to agree it was an act of great violence. And I don’t want that aspect of the film to be thought of as documentary, that makes me angry. It has nothing to do with documentary, nor biography or anything. It’s a kind of memory and imagination.

Going back to color. Let’s start from when you kill it: in the monochrome sepia sequence.

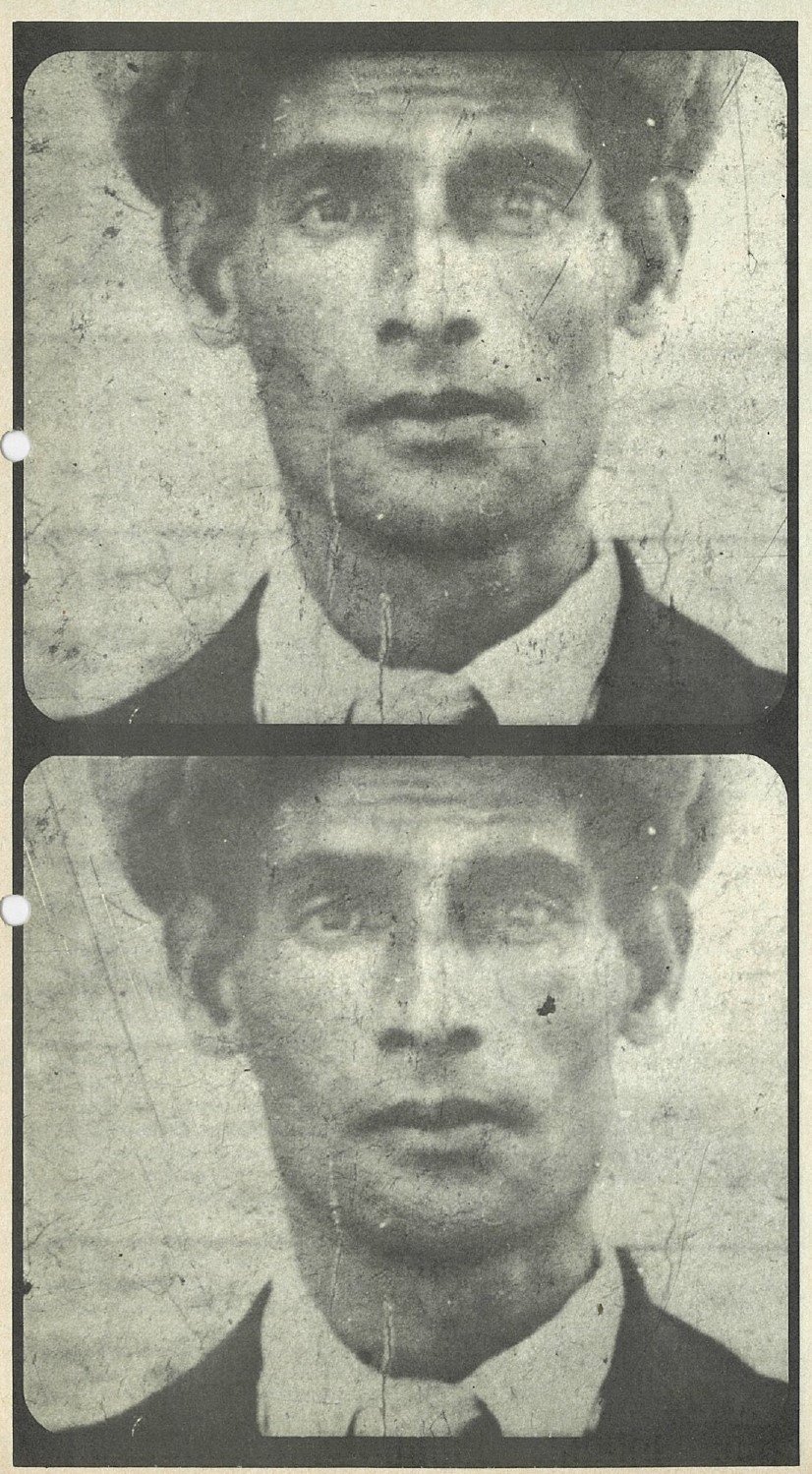

The reasoning behind the sepia is close to the “truth” if you take into consideration a number of factors… Let’s look at some of them: the patients’ brown clothes; the almost metaphysical architectural space; the absence of vital colors in the infirmary; the almost unreal “world” in which Jaime lived, with the joy of placing and relating oneself to it; a nod to the oxidized nobility of the old tones of silent cinema; colorlessness in a color film about colors; an antinomy to the “And I laughed…” sequence and Jaime’s fauve chromatism; the quality of an aquatint engraving; a metaphorical sequence, in flashback, taking place in 1938; an essential tonal raccord to the portrait of the artist, the first photo we see, taken the first year he was interned, and to his first phrase “Nobody, Only Me;” a refining of an immediate and pathetic realism; a reduction which then becomes expansive; a psycho-social hegemony; a poetics and a dignification. . .

NOT HAVING TO EXPLAIN ANYTHING,

IN THE HOPE

If it doesn’t bother you too much, I would like to ask about the structural relationships between the images and sounds in the film.

It’s difficult for me to summarize this structure in words. The structuralists, who are more neutral and methodical, would be more capable of that… You know that in a film that isn’t shot with synchronized sound, the door is left open to one’s wildest imagination or to the most idiotic sound editing imaginable. There’s no complementary relation between image and sound in Jaime. There really isn’t a single redundancy: not even when Louis Armstrong sings, “on a long, white table” and a white table appears (those tables were darkened by many elbows). Speaking of wild imagination and ways of avoiding idiotic sound editing, I would like for us to think about the inclusion of “St. James Infirmary” [the 1956 recording] in the second sequence of the film and in the transition to its third. You know that beyond music, dialogue, noises, we use great forests of silence as sound material. It can be so intense and charged, that silence with timbres like the most hallucinatory of Stockhausen’s.

The image/sound structure creates a permanent transformation. It always takes the moment, the meaning of a shot, a scene, the whole film, further (or beyond). For example: Jaime’s last drawing, the return to the womb, death, it ends with a tracking shot forward, submerged in molten and hammered by Stockhausen’s tam-tam. Well then, the next shot is of a clock on the facade of the hospital that reads one o’clock in the morning (a biographical detail: that is the hour Jaime actually died). You can hear a clock strike, but then, in the psychodrama of the encounter/misencounter at the dye-house, during the impossible farewell of Jaime/Woman, the chimes from two to eight are made by the village bell, announcing the Angelus, tolling for the deceased… At the ninth toll, the chime is once again the clock striking, it’s 9 o’clock, and we’re in a barbershop where the work is carried out with zeal and a former companion of Jaime’s, at the ninth toll/chime, lets his head fall back in repose, evoking the artist.

Without speculating, but because you mentioned structures (and they’re so natural!), I must mention the staging and the action, and their dialectic with the sound: on the second strike, one of the patients (Jaime) lays down two pitchers of coffee, on the third he delicately picks up a dandelion; on the fourth he’ll disappear, forever, behind the sheets (a transparent and opaque border between life and death), on the fifth, sixth, seventh, and eighth, another patient (as if he were a Woman) enters the shot, offers up the first fruits of the land, of love, and is left helpless there carrying the basket… This durée of rural poetics and mysticism, represented by the patients, has successive waves of meaning, which to me is only possible through a dialectic of image/sound, crashing into each other and transforming themselves. It’s vulgar to continue lecturing on “this.” The beauty of it was doing it, discovering it, despairing over it, not having to explain anything, in the hope that others would feel it and hear it too.

HE WOULD SPEND HIS DAYS WRITING

There’s also a permanent relationship between the written elements, the handwriting with a plastic quality, and a phonetic element with a musical quality. But it ends up being tautological: it is still a relationship between images and sounds.

If Jaime’s visual work caused a certain dynamic of the image, his writing caused a different kind of dynamic: either to dream about the phrases he left behind or as an illusory phenomenon which in itself is another visual element of Jaime’s psyche. This also demanded a cinematic approach. It demanded that it be related to Jaime himself and all that that entailed. There’s a sequence that has five different types of writing in a row.

But there’s more: the line in the hospital graph we see, for example, rhymes with the line of the mountain, even though they’re contrary lines: one is broken, full of straight edges, another is curved, filled with smooth contours.

Exactly. That’s very important. Jaime did his visual graphics. The hospital did too, to scientifically determine the state of his health. And there were graphs in nature that were an inspiration to Jaime, that beyond Jaime, have always existed. There’s always a relationship between everything, even in that sequence with the handwritten letters. The envelope is a boat along the Zêzere River, docked at a pier, but at the same time, it’s a necessary raccord for Jaime’s visual art to enter the film for the first time. I needed that element to produce the river but, at the same time, it also served as a springboard to the visual arts. Graphics are in both things. And it’s Jaime’s writing that determines that. These are things that seem to be subtle but aren’t subtle at all. And Jaime didn’t distinguish between the written word and the drawn image. He would spend his days writing.

WE ARE NOT UP FOR AUCTION

I know you’re preparing a film about the Nordeste transmontano [the northeast of Trás-os-Montes], which is precisely called Nordeste. [The film was eventually titled Trás-os-Montes]. Can you say something about that?

I can’t guarantee that it will be a good film like Jaime. What I can say is that we are committed to the same fight, and I consider it an historic duty—out of respect for all the northeasts that still exist in the world—to arrive on time. Losing one’s values of imagination, one’s poetic, ludic, architectural values, the flora and fauna, if we lose this in the Northeast, it’s like losing a natural species forever, and perhaps one day we’ll suffer horribly, imagining them only in photo albums, if there are any. We’ll all become incredibly poor. I wouldn’t care at all if, tomorrow, Portugal had the largest gross national product in the world if the authenticity of the provinces like in the Northeast were lost in the process. I don’t mean authentic in the ethnographic or regionalist way—I mean in what it represents in human value, in civilization, in geographic value, of the earth’s value. I don’t say this lightly, because the Northeast has been in my life since 1957. It’s horrible to save a Romanesque chapiter to put in a museum. A chapiter is part of a column, the column belonged to a portico, a portico belonged to a cathedral, but that, with all its institutions, alienations, and dreams, was still part of a temple inhabited by people. At this time when everything is homogenized, in the worst way, I consider it an extremely serious problem that we are not doing everything in our power to stop that destruction, even if it’s only through a film.

Do you want to make the film in 16 or 35mm?

The plastic force, the telluric force of the province countryside is so great that only 35mm film would be useful for us.

Direct sound?

No. The Northeast has a lot of sound which is no longer the sound of the Northeast. We want to recreate sound according to the sound the Northeast had, or should have. You’ll say that it’s a distortion of reality, but in our dreams we don’t intend to reach an absolute truth…

I’ll interrupt you to fit in a Novalis quote: “The more poetic, the more real.” That’s my only deep conviction.

…It’s a kind of respect for the stone that’s crumbling away, but if we have a sense of the stone, it’s because we’ve hit it a lot, hit our heads on it countless times. The stone, the wood, the people who invented poems, the people who sowed, the people who watch their children leave, and watch their rivers lose their fish, who kill and are killed. Passionately. I can’t coldly imagine how long the picture might be right now. Determining the duration of a film a priori seems ridiculous to me. The length of a film is internal and has nothing to do with the physiological length of a projection. A piece of bread with olives can be much tastier than the richest “menu.” A haiku can have three verses and be more poetic than a long epic poem.

Unfortunately, we’ve all been complicit in this lie. I believe the erosion of the Northeast is not only an erosion from the wind, the sun, and the soil that the floods carry away. It’s a more total erosion, but you start to see that underneath that erosion, there’s a lot that’s not eroded, not learned, and above it, many birds fly, many men walk and dream. The Northeast is up for auction. Everything is being auctioned off, and there are certain things you can’t sell, even if it’s to “save” them, for those who are going to buy pieces and put them in their houses. We’re not up for auction. Our responsibility is not up for auction. I don’t say this to make it everybody’s motto, but for me, it’s crucial. The way it can be crucial to build beautiful cinemas in urban areas. What we need is to discover the northeasts of Lisbon. They also exist there.

I don’t want to talk about what I consider ambitious, because sometimes describing things robs them of their emotion, but that’s not all: there are many opportunists and even more adventurers, and as a Dogon proverb says, the foreigner only sees what he knows. And really, you can’t judge based on what you know. What they’re doing to ethnography––I’m not saying to the people––is shameless and shameful. In fact, ethnography is only interesting as research, an ethnographic program in the Northeast doesn’t interest me. If it’s a fictional anthropology, then that’s fine, even if it seems paradoxical.

Are your well irate verbs a response to the attacks that some TV morons have perpetrated on this country, or are you, on the contrary, just waking from a dismal dream?

I’m talking about the attack of television, among other things. One thing people know: it’s when we’re offended. If they don’t already know, if we think we know something they don’t, we are obliged to feel offended… Or let the bolts of lightning rain down, let the erosion take everything with it.

Your lips to God’s ears, and on that surety, I propose that the interview begin here. However, in order for it to begin, it must end. So let’s get back to Jaime, so that it ends well. At the end of the film, you frame the cross-like bars of Jaime’s cell and cut to a photograph of Jaime, which is the last shot of the film, just as the first is a photograph of Jaime. Everything that happened, happened, in the end, between two photographs, two stills of a man’s life.

It was important to place his portrait at the end. He wrote: “Animals like portraits of princes Eyes set on the same arks…”

— end ––