March 20 - 26, 2026 at Anthology Film Archives, co-programmed by Ethan Spigland & Edward McCarry

In his 1957 review of Frank Tashlin’s Hollywood or Bust (1956), Jean-Luc Godard described Jerry Lewis’s face as one “where the height of artifice blends at times with the nobility of true documentary.” Godard was, in a sense, prophesying the films he would later make, where the same dialectic can be found: an oft-overlooked strain of improvisation, bald-faced artifice, and pure antics coexisting with unvarnished reality. To pay tribute to these two contemporaries and their deep entanglements, we present a series of double features pairing films by Lewis and Godard. Both turned comedy into a form of modernist experimentation: Lewis through his elastic body, elaborate gags, and self-reflexive use of technology; Godard through his deconstruction of genre and his playful, anarchic sense of form. Each viewed cinema as a laboratory for testing the boundaries between art and entertainment, sincerity and absurdity, self and persona. Seen together, their films reveal a shared commitment to invention and a profound suspicion of the very illusions they so brilliantly created. We hope the encounter activates their respective work in new and explosive ways—and perhaps, as Lewis once dreamed, offers the chance to “say something on emulsion that will stop a soldier from firing into nine children somewhere, sometime. Now; next year; five years from now.”

Related texts

The Big Mouth Strikes Again: A Dialogue on Mid-period Jerry Lewis by Chris Fujiwara and A.S. Hamrah

Program 1

Hollywood or Bust

Dir. Frank Tashlin

1956. 95 min. DCP.

In English.

Cartoonist-turned-motion picture director Frank Tashlin was the single most important influence on Jerry Lewis. A subtle and serious mind gifted in the arts of exaggeration, Tashlin’s subject was “the nonsense of what we call civilization.” He frequently turned his camera on the moviemaking apparatus itself—the stuff illusions are made of. In Hollywood or Bust, Lewis and Dean Martin, in their last film together, take a road trip from New York to Hollywood in a red convertible. Along the way there is singing, gambling, bullfighting, Anita Ekberg, and scenes at the limits of absurdity. To close his 1957 review of the film in Cahiers du Cinéma, Godard declared: “And henceforth, when you talk about a comedy, don’t say ‘It’s Chaplinesque’; say, loud and clear, ‘It’s Tashlinesque.’”

with:

Pierrot le fou

Dir. Jean-Luc Godard

1965. 110 min. 35mm.

In French with English subtitles.

“A completely spontaneous film. I have never been so worried as I was two days before shooting began. I had nothing, nothing at all… The whole thing was shot, let's say, like in the days of Mack Sennett.” A riot of improvisation, Pierrot le fou is an adventure film of an absolute sort, rife with risk and danger at every moment of its creation. Anna Karina and Jean-Paul Belmondo, “the last romantic couple,” reject polite society and make off to the seashore in a variety of stolen candy-colored cars. The fugitive couple moves through a succession of episodes that play off each other with unresolved tension. In a letter to Godard, Frank Tashlin once wrote: “The more I understand the cinema, the more I realize it is an art which is dangerous to take too lightly.”

Program 2

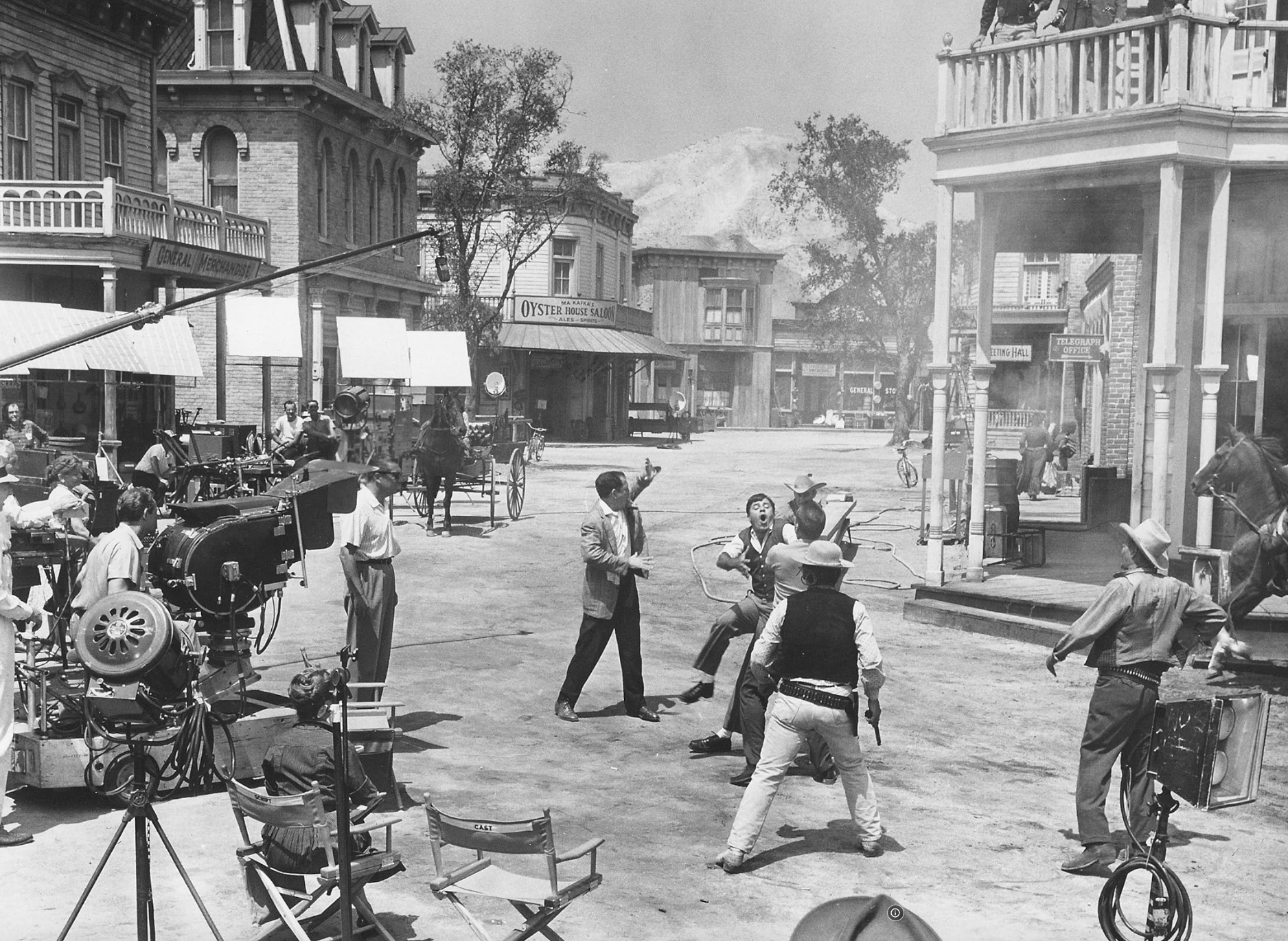

The Errand Boy

Dir. Jerry Lewis

1961. 92 min. 35mm.

In English.

Playing a hapless messenger let loose on the Paramount lot, Jerry Lewis collapses the boundary between labor and spectacle, turning everyday work into comic choreography. Both a satire of the dream factory and a meta-cinematic reflection on his own role as star-director, The Errand Boy reveals Lewis’s Brechtian touch, where the machinery of filmmaking exposes the fragile artifice of its own illusion. Like Godard’s Contempt (1963), made two years later, the film exposes the contradictions at the heart of cinematic production: art caught between play and labor, creation and commerce. Both filmmakers lay bare the pathos and poetry of making images in a world ruled by spectacle.

with:

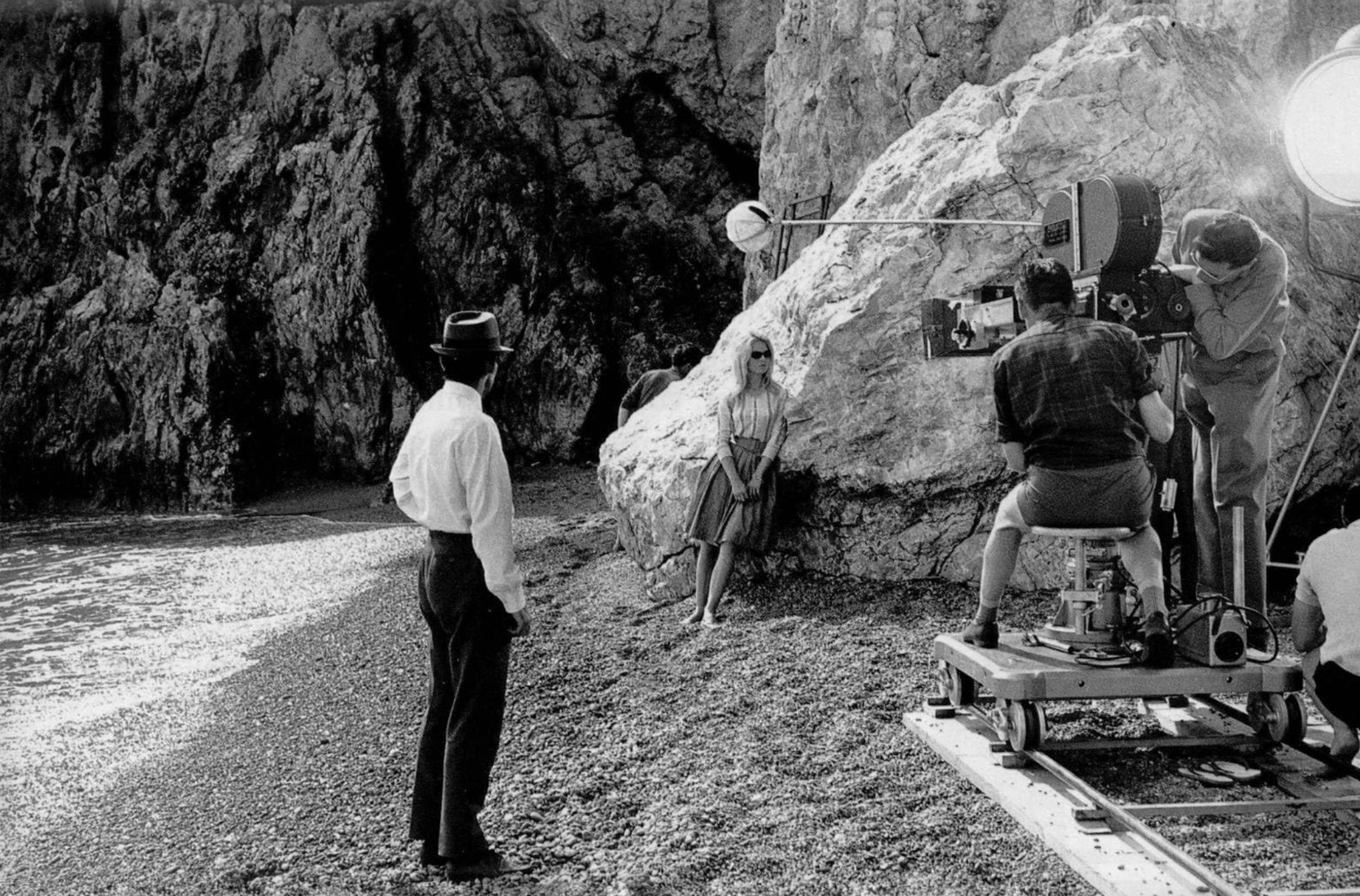

Le Mépris (Contempt)

Dir. Jean-Luc Godard

1963. 102 min. DCP.

In French with English subtitles.

In Contempt, Jean-Luc Godard transforms the disintegration of a marriage into a sweeping meditation on art, commerce, and modern alienation. A subversive deconstruction of commercial filmmaking, the film stars Michel Piccoli as a screenwriter caught between a proud European director (played by Fritz Lang), a crass American producer (Jack Palance), and his increasingly distant wife, Camille (Brigitte Bardot). Set between the decaying grandeur of Cinecittà Studios and the sun-drenched beauty of Capri, Contempt unfolds as both a star-studded Cinemascope epic and an intimate study of love undone by the machinery of cinema itself.

Program 3

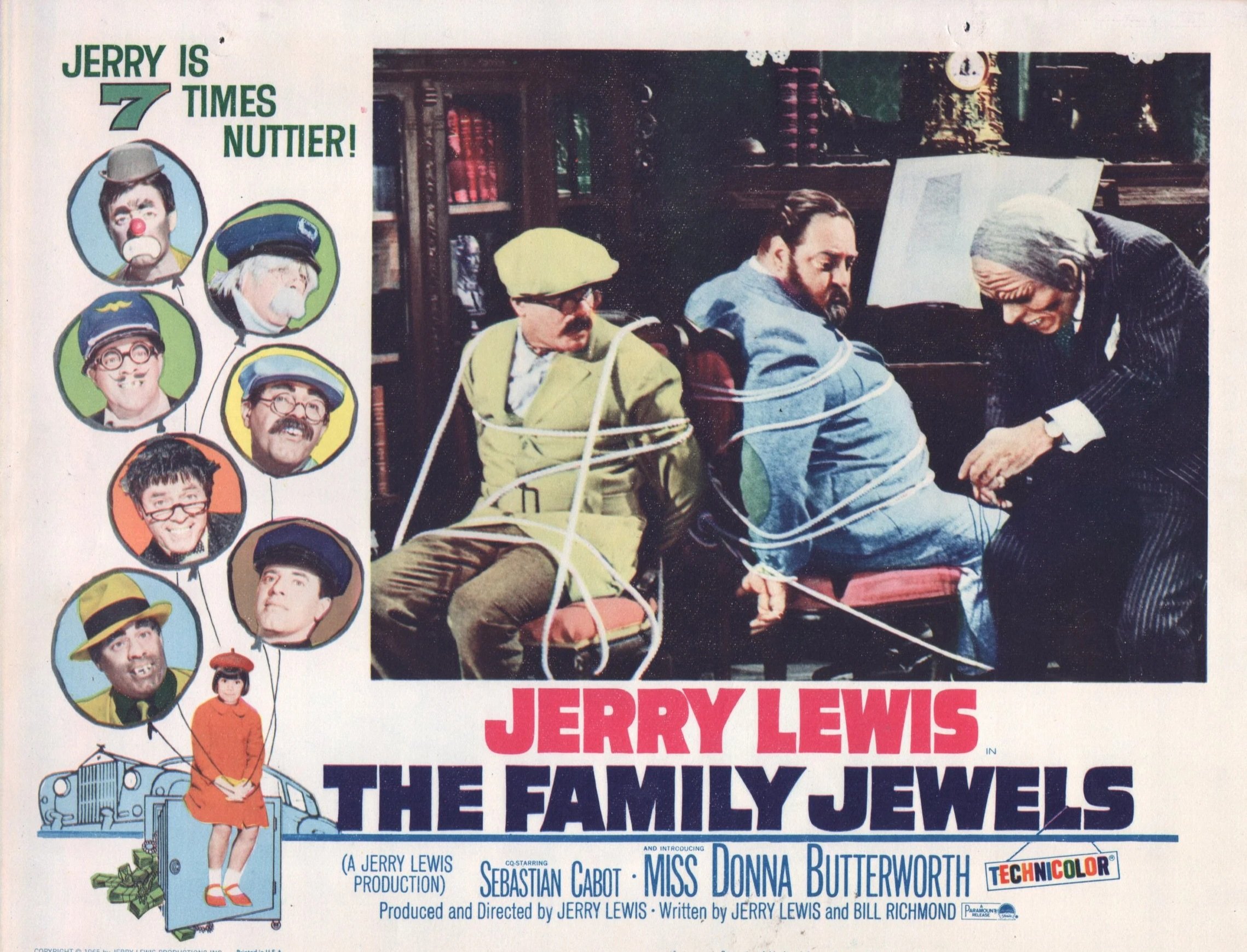

The Family Jewels

Dir. Jerry Lewis

1965. 99 min. DCP.

In English.

The Family Jewels, a zany tour de force, showcases Jerry Lewis’s virtuosity as both performer and director. The film follows a young heiress, Donna Peyton, who must choose a guardian from among her six eccentric uncles, all played by Lewis, each embodying a distinct comic archetype. As Donna visits each in turn, their absurdities become a playful meditation on identity and performance. Blending slapstick, pathos, and reflexive humor, The Family Jewels stands as a dazzling showcase for Lewis’s comic inventiveness. His painterly use of color and precise, architectural framing would leave a lasting impression on Jean-Luc Godard, who shared Lewis’s fascination with the multiplicity of the self.

with:

Made in U.S.A.

Dir. Jean-Luc Godard

1966. 90 min. 35mm.

In French with English subtitles.

A delirious pop-art noir, Made in U.S.A. transforms the pulp detective film into a dazzling collage of color, politics, and cinematic references. Anna Karina plays a Bogart-like private eye drifting through a candy-colored landscape of slogans, comic panels, and ideological confusion—a vision of America as pure image. Drawing on the painterly use of bold color and the stylized physical comedy of Jerry Lewis, Godard turns cinematic artifice into a mode of critique. Made in U.S.A. stands at the threshold of Godard’s transition from narrative deconstruction to revolutionary form: a film where color, gesture, and absurdity become instruments of subversion.

Program 4

The Ladies Man

Dir. Jerry Lewis

1961. 95 min. DCP.

In English.

In The Ladies Man, Jerry Lewis constructs an enormous dollhouse-like set—a four-story boarding house teeming with women—through which his awkward, shy protagonist, Herbert H. Heebert, wanders in wonder and bemusement. Lewis reimagines slapstick as an exploration of space, gender, and reflexivity. Anticipating Godard’s Tout va bien, Lewis treats cinematic architecture as a social laboratory, where comedy becomes a means of probing performance, alienation, and the precarious order of modern existence.

with:

Tout va bien

Dirs. Jean-Luc Godard & Jean-Pierre Gorin

1972. 95 min. Format TBD.

In French and English with English subtitles.

Made in the aftermath of May ’68, Tout va bien examines the intersections of class struggle, media, and intimacy through the breakdown of a couple (Jane Fonda and Yves Montand) caught in a factory strike. Combining political analysis with formal experimentation, Godard and Gorin transform the factory into a cross-sectioned set—an explicit homage to the dollhouse structure of Jerry Lewis’s The Ladies Man. As the camera tracks laterally through this exposed architecture, the film lays bare the workings of ideology and desire.

Program 5

Smorgasbord (aka Cracking Up)

Dir. Jerry Lewis

1983. 89 min. 35mm.

In English.

Jerry Lewis stars as Warren Nefron, a hapless man so overwhelmed by modern life that he repeatedly tries (and fails) to end it. Beneath its chaotic surface lies a sense of despair and alienation, as Lewis turns his trademark clown persona inward, exploring themes of failure and the collapse of control. The film’s disjointed structure, deadpan absurdity, and reflexive humor anticipate Jean-Luc Godard’s Keep Your Right Up (1987), in which Godard similarly recasts the filmmaker as a clown adrift in a universe of unraveling meaning. Both artists turn comedy into philosophy, finding, within absurd repetition and breakdown, a darkly comic portrait of modern existence and a fragile faith in cinema itself.

with:

Soigne ta droite (Keep Your Right Up)

Dir. Jean-Luc Godard

1987. 82 min. 35mm.

In French with English subtitles.

Keep Your Right Up is a delirious fusion of slapstick, philosophy, and pop performance. Playing “the Idiot”—a filmmaker modeled on Dostoevsky’s Prince Myshkin—and channeling Jerry Lewis, Godard turns everyday gestures into comic studies of the body as a malfunctioning machine. The French band Les Rita Mitsouko strives to find the right harmony. A solitary man seeks connection with others, yet feels he has landed on the wrong planet. A group of travelers, like Ulysses before them, tries to reach its destination. One of Godard’s funniest and most overlooked works, the film becomes a meditation on art, speed, and existence, transforming physical comedy into metaphysical reflection.

Program 6

The Nutty Professor

Dir. Jerry Lewis

1963.107 min. DCP.

In English.

Jerry Lewis’s The Nutty Professor transforms the Jekyll and Hyde story into an incisive comedy about performance, identity and the constructed self. Beneath the slapstick lies a sharp reflection on masculinity and self-invention through artifice. In dialogue with Godard’s Nouvelle Vague (1990), Lewis’s film reveals cinema’s fascination with doubling—the split between the authentic and the manufactured, the self and its image. Whereas Lewis externalizes this tension through comic exaggeration, Godard internalizes it as haunting repetition. Both explore subjectivity as something always in flux.

with:

Nouvelle vague

Dir. Jean-Luc Godard

1990. 89 min. 35mm.

In French with English subtitles.

Jean-Luc Godard’s Nouvelle Vague (1990) revisits the theme of the double through the spectral presence of Alain Delon, who reappears as two incarnations of the same man, Godard transforms this narrative of death and return into an allegory of cinema itself—its repetition, mirroring, and resurrection through images. The film’s fragmented dialogue and reflective surfaces turn identity into a play of echoes and reversals. Paired with Jerry Lewis’s The Nutty Professor, Nouvelle Vague appears as its philosophical mirror: where Lewis celebrates transformation through performance, Godard reflects on repetition and return.

Program 7

Three on a Couch

Dir. Jerry Lewis

1966. 109 min. 35mm.

In English.

As both director and star, Jerry Lewis fuses inventive slapstick with Freudian farce, turning the trappings of 1960s domestic comedy inside out. Playing a psychiatrist who adopts multiple identities to “cure” his fiancée’s neurotic patients, Lewis exposes the porous boundary between role-playing, desire, and the self. Like Anne-Marie Miéville’s After the Reconciliation (1989), the film stages the impossibility of harmony between the sexes within the very medium of dialogue. Both filmmakers treat language as a structural impasse—where speech yields not resolution but an endless play of misunderstanding.

with:

Après la réconciliation (After the Reconciliation)

Dir. Anne-Marie Miéville

2000. 74 min. DCP.

In French with English subtitles.

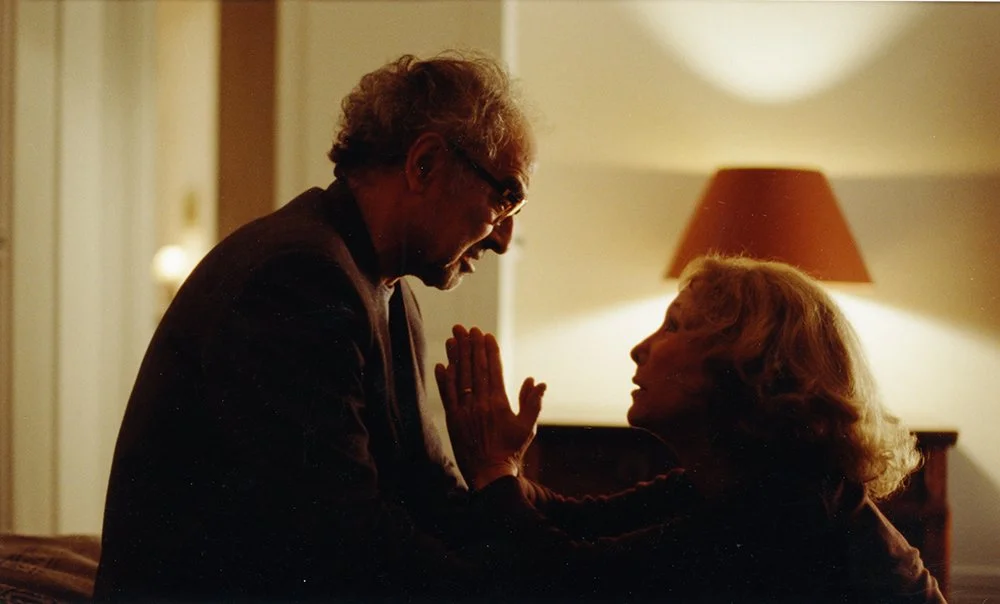

In After the Reconciliation (1989), Anne-Marie Miéville—Jean-Luc Godard’s longtime partner and collaborator—transforms the everyday exchanges between men and women into a lucid meditation on love, language, and the difficulty of understanding. Staged almost entirely in conversation, and featuring Miéville and Godard among the cast, the film follows four characters whose attempts to speak through their disappointments reveal the limits of desire and language. Infused with literary and philosophical allusions to Conrad, Heidegger, and Tolstoy, Miéville’s film is at once philosophical and tender, exposing how intimacy and communication, like cinema itself, are forever on the verge of collapse.

Special thanks to Jed Rapfogel (Anthology Film Archives) and Jake Perlin (The Film Desk).