Joaquim Pinto on António Reis & Margarida Cordeiro

Joaquim Pinto, 2025

Interviewed by Edward McCarry

Joaquim Pinto is a sound recordist and designer, a director, and a producer. He has been a key force of Portuguese cinema for the past 40 years, a collaborator and fellow traveler of many great filmmakers of this period, notably João César Monteiro, and an exceptional director in his own right. Like Pedro Costa, he was a student of António Reis at Lisbon’s Escola Superior de Teatro e Cinema, later recording and mixing the sound for Reis and Margarida Cordeiro’s second feature, Ana (1982). The following remarks were written over email in January 2025.

This text accompanies Peasants of the Cinema: António Reis & Margarida Cordeiro

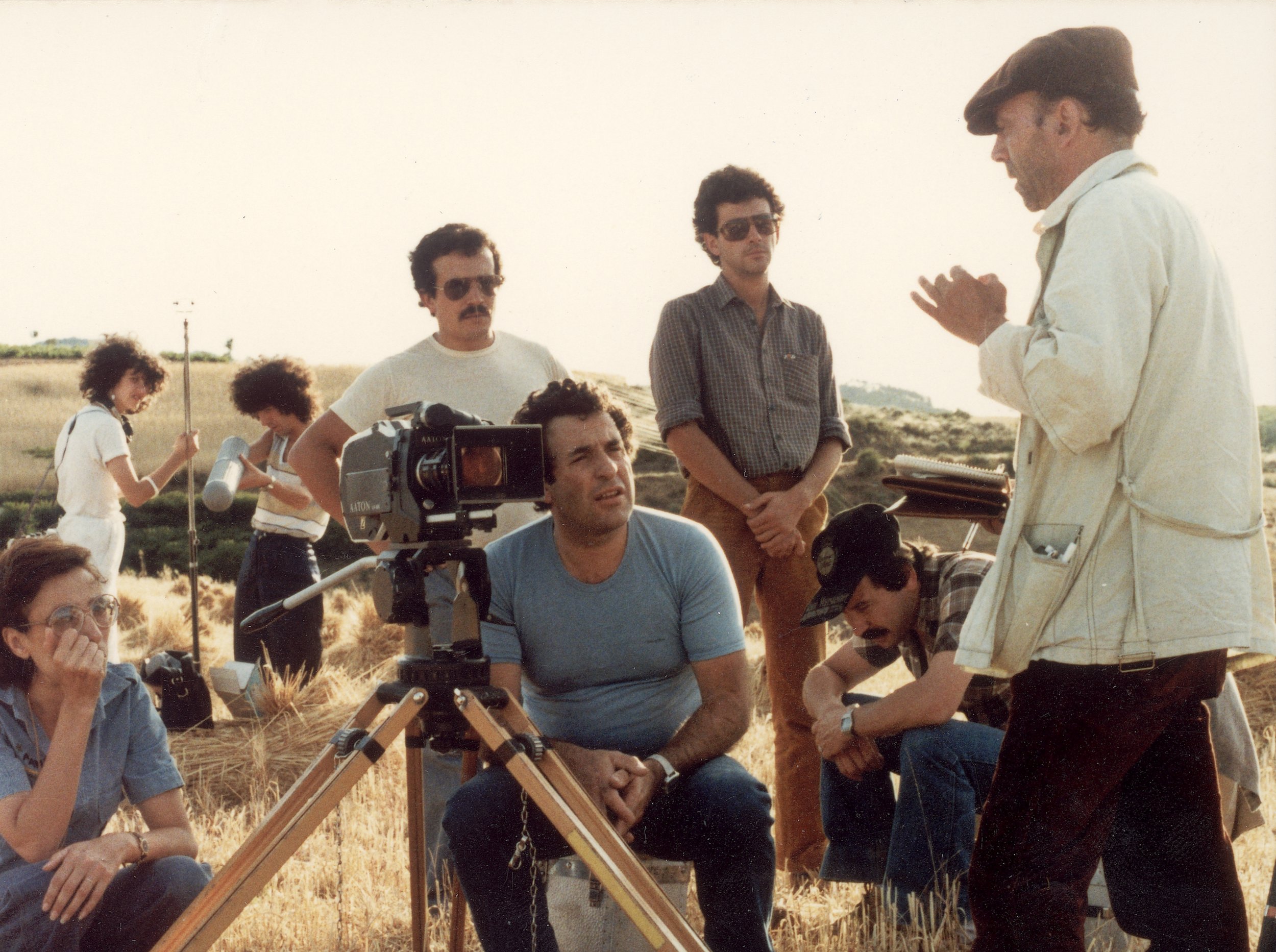

António Reis (far right) on the set of Ana (1982). Courtesy Cinemateca Portuguesa.

Edward McCarry: Can you talk about your first encounter with António Reis and Margarida Cordeiro? How did you end up working with them?

Joaquim Pinto: I saw their first film, a documentary called Jaime, weeks after the revolution in 1974, the end of an almost 50-year dictatorship in Portugal. I was in the last year of high school. I was overwhelmed by the film’s subject and beauty, by Jaime Fernandes' drawings and obsessions. I soon found out that the director, António Reis, was the same young poet I heard about in my childhood in Porto. Some time later, I discovered that he and Margarida were shooting in Trás-os-Montes. My mother’s family is from that remote province. I had spent long periods with my grandparents there, and had strong memories of happiness. Reis and Margarida were shooting with the younger brother of my best friend; he was a main character in their film [Trás-os-Montes (1976)].

I soon joined the Film School in Lisbon, and having Reis as a teacher of film analysis and editing felt like reconnecting with an old acquaintance. Reis had a close relationship with his students. I remember accompanying him home quite often after classes, spending hours with him and Margarida, talking about such disparate subjects as art, history, poetry, films, and politics.

I specialized in sound for film, and soon after I left school, they invited me to work with them [on Ana].

What’s striking about the sound in Ana is how delicate it is. Slight movements, like Ana walking across a room or combing her grandchildren’s hair, have a strange resonance. This is true in the interiors, of course, but even in the landscapes, the sound has a certain heat, a closeness. Were Reis and Cordeiro looking for rawness in the sound? Was sound always recorded directly with the image?

Reis and Ana called me when they were editing Ana. They asked me to look at the first edit and help them with the sound. Most of the sequences had been recorded without sound, and others had terrible sound quality. They were apprehensive. The science fiction film Tron was being shot that same year and I had read an article in American Cinematographer about its production. They had, for the first time, re-recorded most of the effects in real life conditions, using a video copy of the edit as a cue.

I challenged Reis and Margarida to go back to Trás-os-Montes with me, to re-record all the location sounds in the same spots. We chose the same time of the year and spent two months there together. I split my time between recording and taking care of their very young daughter. They would be present for some recordings, but in other cases, they would let me work alone in my search for sounds that were true to the places and that would fit the mood of the scenes. After dinner, we discussed Michel Chion’s “La musique électroacoustique,” which had just been published. I later travelled again by myself for the last recordings. Funny you mention “rawness.” Yes, I intended to keep that “raw”—or should I call it “brut”—side to it, which is so present in their images and in those places.

Then, there was several weeks at the editing table in order to rebuild the soundtrack and to synchronize the sounds to the picture. We would watch every scene together, then they would let me do the precision work. So, most of the sound for Ana was not recorded with the image. We were editing in 16mm (I would rather do it in 35mm, a more precise format for sound editing) and I vividly remember one full afternoon spent synchronizing, one by one, the splashes of the paddle from a small row boat. Since we could only listen to two tracks at the same time, my method was to display all the sounds in a sort of mix chart, a sound score that would allow us to talk about concepts and ideas before the real work was done.

Mixing the film was also exciting. We mixed at the old (now demolished) Billancourt Studios in Paris, where Jean Cocteau had shot Beauty and the Beast. The sound mixer was Antoine Bonfanti, who had recorded most of the nouvelle vague films. He had a way of working that went against most of the sound mixers of the 80s, who were very analytical. He liked to mix very fast, so I would read my mix charts to him in advance, telling him which sounds were about to arrive at the mixing desk. Sound editing and track disposition was logically done, and we managed a feat: mixing in two days what would normally take two weeks. Bonfanti became a good friend of mine, up until his death.

One last remark: since Ana was shot in 16mm, we mixed with an “Academy filter” before the speakers, which would limit the high frequencies to 8kHz in order to mimic the severe limitations of 16mm optical sound. I hope, if a restoration and DCP is produced, they can go back to the full spark of the original magnetic sound mix. I only heard the full spectrum mix once the work was completed—it was a moment of pure joy.

There’s a dialectic of sounds in Ana. The voice-overs collide with the sounds of the house, of the land, the wind, often uneasily. Or the Magnificat of Bach, for instance, it’s a sharp intervention in the soundtrack. Was this something Reis and Cordeiro discussed with you?

Those were their choices; we discussed them in the process of sound editing. They were fundamental to the soundtrack, and I suppose those decisions were made clear by the editing and mix. Instead of trying to ease them out, Bonfanti’s mix assumed them frontally. Please note that Bonfanti had recorded and mixed, for instance, Pierrot le fou, where abrupt music cuts, voice-overs, location sound, sudden explosions, talk to each other. Bonfanti did not know our film or its sounds beforehand, so we would talk together on coffee breaks. I would spread my mix sheets over the table and explain the concepts behind the sounds, then we would go to the studio and Bonfanti would say on plonge! (Let’s dive!). At the next table, a young Jane Birkin, who was shooting at the same sound stage, would look at us quite amused.

What did you learn from Reis and Cordeiro?

I guess I learned a poetic approach to life. Margarida is not mentioned so often, but she was a really creative force behind their films. She had an incredible, dark sense of humor. She would balance Reis’ sometimes nervous and obsessive approach to work, and they made a perfect match. It showed me that creative cooperation and mutual love are possible, and it set an example for my future life.

Let me tell you one more detail. After António Reis died, Margarida tried to go ahead with a project they had been working on together, an adaptation of Juan Rulfo’s novel Pedro Páramo. I was on the Portuguese Film Institute jury when she applied alone for funding for its production.

Contrary to the other members of the jury, I had worked with them and knew that the shooting was well prepared and that she was perfectly able to direct it alone. But I could not convince anyone that she was an experienced director, and how important it was that she continue their work. I was alone and everyone voted against me. They feared it was too risky to “give her money,” adding that she was a woman. Can you believe it?

- end -