A Letter to the Tokushima Shimbun

Paulo Rocha, 1982

The following is an account by Paulo Rocha of the origins of his film The Island of Loves, written in English. It is addressed to the Tokushima Shimbun, a local newspaper from the city of Tokushima, Japan, where Rocha first encountered the work of Wenceslau de Moraes.

The document was generously scanned from the collection of the Cinemateca Portuguesa and is republished here with their permission. Special thanks to Joana de Sousa.

This text accompanies Two Evenings for Sumiko Haneda & Paulo Rocha, a dual program featuring Rocha’s The Island of Loves and Haneda’s The Poem of Hayachine Valley. March 13 - 14, 2026 at Japan Society & Light Industry.

To the Tokushima Shimbun

care of Mr. Sugita Takuji

On the film “Koi no Ukishima”

When I came for the first time to Tokushima, in 1967, I could not imagine that my life would be for such a long time kept revolving around it [sic].

I had came to Japan at that time, because of a film I was preparing about the introduction of firearms in Tanegashima by the Portuguese, in the XVI century: Teppo Denrai Monogatari, as told by F. Mendes Pinto, the Portuguese adventurer who brought to Japan Francis Xavier. Pinto’s travels book the “Tōyōki” became one of the greatest travel books of western literature.

The script was by myself and by Takano Etsuko, an old friend from school time in Paris. Daiei got on that script a generous grant by the Japanese government to promote international films, but that company’s financial problems prevented it from treating the project as a “serious film.” Negotiations broke down, the Daiei “Teppō” film was a flop, and I was left with empty hands.

At that time, the then Portuguese Ambassador to Japan, Armando Martins, urged me to visit Tokushima. I have seen in Moraes, walking in Igacho and in the slopes of Mount Bizan, the books of Moraes began little by little to become live inside my head.

Soon I was possessed by the urge to analyse in a film the complex personality of Moraes, his friends, and the women he loved in Lisbon, Macau and Japan. I traveled around the world to the places where he had stayed before he came to Japan. I visited Mozambique, Macau, Singapore, and other places. I read hundreds of books about his times, his works, his friends, the countries he had stayed. I started seriously studying the Japanese language, in order to be able to understand a little more about the country and the people he had loved most. And, most importantly, I tried to find the money necessary to finance a film as expensive as this one, with locations in so many countries.

At that time, I was still an [sic] young filmmaker, but I was fairly well known in my own country, because of the success of my first two films, and my career, inside the country, seemed an easy one. But it was quite a different matter to finance a film who [sic] would cost five or seven times the budget of a [sic] average Portuguese film.

The oil shock and the 1974 Revolution brought difficult times to the Portuguese economy, and during 3 or 4 years it became impossible to convert Portuguese money into foreign currencies.

After the Revolution, the government decided to strengthen the cultural ties with other countries, and I was asked to come to the Portuguese Embassy in Japan. It was a good opportunity to know better [sic] a country I had visited 3 times in the past, and also to prepare for the film of Moraes. Now, so many years later, and when the shooting of the film is over, I keep asking to myself [sic] what strange obsession obliged me during such a long time not to drop this hopelessly difficult project and settle back home again making films without special problems, in Lisbon, as everybody over there thinks I should be doing. This is a mystery I will never solve. Perhaps the spirit of Moraes himself took over this project and would not allow me to get free before completing it.

Well… you will keep asking me again: “But… why Moraes?”

Moraes was the last of a glorious line of Portuguese who since the beginning of the XVI century wrote about Asia so many important books [sic]. He was also a fascinating man. His blend of tenderness and egoism, of love and aloofness, of artistry and casualness, of sacred and profane, of peace and despair, make him an unforgettable personality.

The XIX century Portugal he was born into, was a troubled and proud country, looking back to its epic past of navigations and discoveries, and a country overridden by a dark pessimism about the future of the Nation [sic]. As a young navy officer placed in overseas territories, Moraes became little by little convinced that the hardpressed peoples and cultures of Asia could give better answers to the problems of mankind than the proud Europe then at the zenith of its power and glory. He foresaw a more balanced time when white men would no longer rule the world. In his eyes Japan was the country that in many aspects pointed the way other asian nations should follow in preserving their own culture and daily life from outside influences.

He found in Tokushima inspiration for his greatest books: O "Bon-Odori" em Tokushima and O-Yoné e Kó-Haru. His most important themes: nature, love, memory, death, the passing of time, were refined by the terrible experience of the death of two women he loved, both of them women from Tokushima.

In Tokushima he perfected the Portuguese language with refinements from the esthetic tradition of Japan. His Tokushima books became superior examples of modern wabi, sabi, karumi, nagare, and so on. No other foreign writer has ever repeated this feat. Because of this, the Portuguese language acquired a musicality and delicacy it did not possess before.

His portraits of Kó-Haru and O-yoné, in their apparent simplicity, make them more rich of mystery and more haunting than the characters of most masterpieces by famous novelists.

When I started to search for a staff, and for actors for the film, I was very much afraid. As a rule, foreign films made in Japan with the help of Japanese professionals, run into every kind of misunderstandings and troubles [sic]. I was very, very lucky, to find the best kind of help I could hope for: talented, dedicated men and women, that worked hard and in harmony, to make this long film in the short time of 3 weeks. With limited means, we were able to shoot 2 hours of high quality film, notwithstanding the problems derived from the actors using either Japanese, or Portuguese, or English, or Chinese language [sic].

In Tokushima we had a very warm welcome and effective help from the man in the street to the most important people in town, and that we will never be able to forget. As my expressions of thanks I hope the film will be a good one, and that the people of Tokushima will like it.

- Paulo Rocha

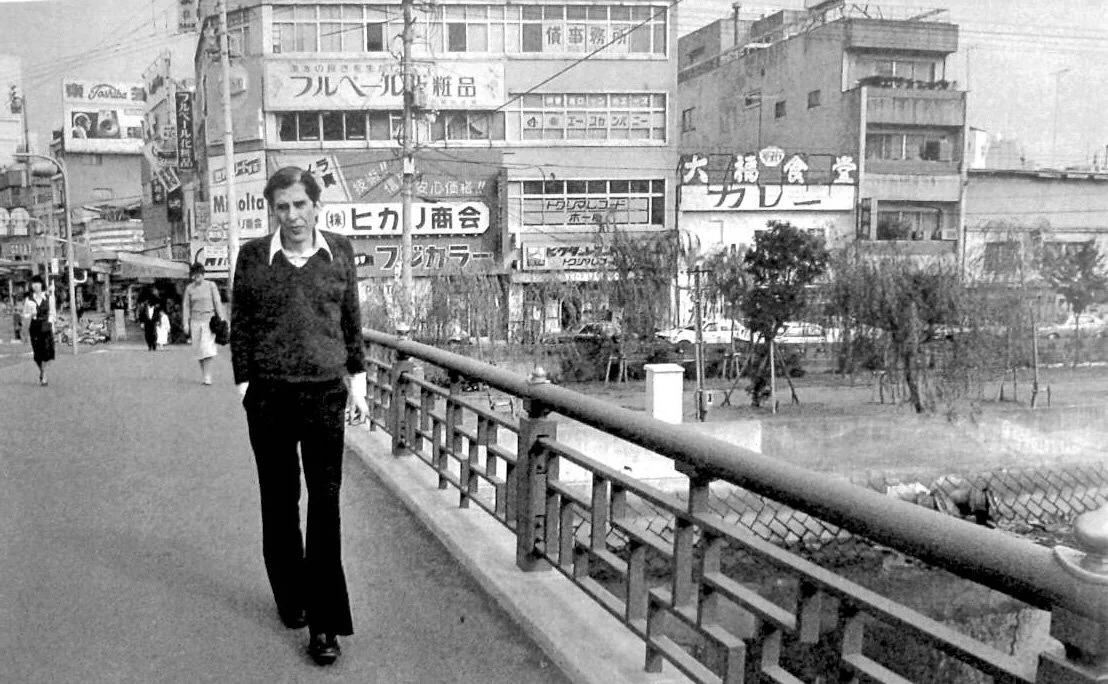

Paulo Rocha in Tokushima, 1981

x